These days everyone is a photographer. Have you noticed? If you are a 21st-century photographer with a cell phone, you’re posting your photos on Facebook, Instagram, and Photobucket. And a lot of the photos are quite good. It was not always this way.

Do you remember the days of 35 millimeter Leicas and Nikons? Of lens openings and shutter speeds? Of depth of field and “pushing” the film’s developing time in the darkroom? If you remember these arcane terms and actions, you are much like I am. And you may miss those good old days.

To me, being a photographer these days is just too easy. There are so many pointing smartphones at this and that, taking selfies, and marveling at the results. Yes, I miss those good old days of real photographers.

But do you know that San Francisco has been a haven for real photographers, using real cameras, since shortly after the Gold Rush? This city is famous for famous photographers. Let me tell you about some of them.

ARNOLD GENTHE

A member of an academic family in Berlin, Genthe immigrated to San Francisco in 1895 to become the tutor for a young man from a German family. In his off hours, Genthe explored the city, especially the enclave known by its Chinese name, Tangrenbu. The locals called it Chinatown, and Genthe was attracted to it because to him, and other outsiders, it appeared strange and exotic. Soon he acquired a camera and became a regular presence in Chinatown, photographing the inhabitants.

Genthe professed to shoot his Chinatown photos candidly, but studying his classic, now famous glass plate negatives and prints, one realizes two important factors: First, most of the photos were taken on Chinese holidays, apparent because many inhabitants were wearing Chinese holiday garb. So for the most part, Genthe wasn’t recording the usual day-to-day street life. Second, Genthe carefully scratched out or erased from his glass negatives any representation of Western culture that appeared in the frame.

These two factors discredit his desire to have his photos appear as candid representations. Nevertheless, his contribution is immense in depicting life in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1880s and 1890s. And not only are his Tangrenbu photographs an important record but a beautiful one as well. He is also famed for shooting some of the most memorable photos of the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire.

EADWEARD MUYBRIDGE

In the 1870s, railroad baron and former California governor Leland Stanford made an intriguing wager with a friend that ultimately led to what we know today as movies.

Stanford bet $25,000 that at full gallop all four of a horse’s hooves are off the ground at the same time. All he had to do was prove it. On Stanford’s Palo Alto estate in 1878, an English-born photographer Eadweard Muybridge rigged a series of 24 cameras and set them to release their shutters in sequence when one of Stanford’s thoroughbreds, Sallie Gardner, galloped by. The experiment proved two things. First, Stanford was correct in his assumption about galloping horses. But it was the second discovery that led to what we know today as Hollywood: Motion could be reproduced in a realistic fashion.

Muybridge, with financial aid from an enthusiastic Stanford, then constructed a primitive, sequential photo projector called the zoopraziscope. Two years later, Muybridge presented the first public movie screening on May 4, 1880. It was held at the San Francisco Art Association Exhibit Hall on Pine Street and was called Illustrated Photographs in Motion. Admission was 50 cents. The show featured the thoroughbred Sallie Gardner and a gymnast named William Lawton. Sally was the precursor to Lassie, Lawton to Arnold Schwarzenegger.

IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM

Born in Portland, Ore., in 1883, and after graduating with a degree in chemistry from the University of Washington in Seattle, and already interested in photography, Cunningham worked for the great photographer of American Indians, Edward S. Curtis. With Curtis, she refined her desire to be a photographer, then married artist-teacher Roi Partridge and moved to San Francisco.

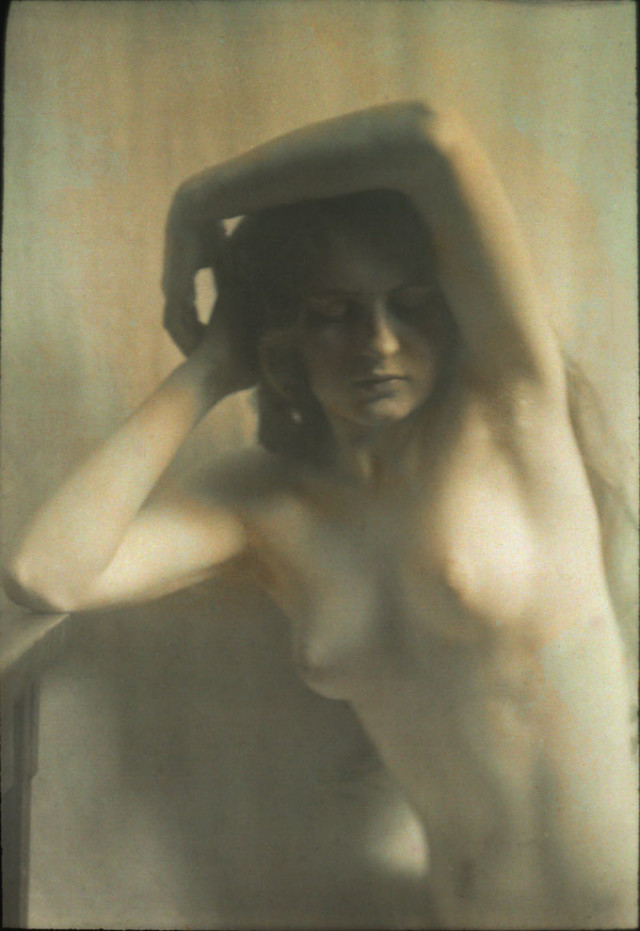

Her botanical photographs, as well as nudes and landscapes, attracted attention, and she co-founded Group f/64, a collective of like-minded San Francisco photographers. They took the unusual group name from a large-format camera’s smallest aperture setting, which, when used adroitly, produced photos of amazing sharpness and clarity. Cunningham’s work is found in many museums and private collections. Her detailed close-ups in sharp black and white are haunting and evocative of an almost surreal universe.

Other members of the Group f/64 collective included Edward Weston and Ansel Adams — the latter of whom is discussed in more detail next month along with additional famous photographers with a San Francisco connection.