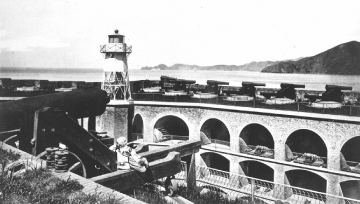

Fort Point: The Civil War fortress that was not needed

The Golden Gate Bridge had not yet been built, of course, but this key fort among a number of others designed to protect residents, the harbor and the area’s gold was ready for action. The enemy? Not Great Britain or other foreign invaders as originally intended, but the Confederacy, which by announcing its secession from the Union signaled the beginning of the bloodiest war in United States history.

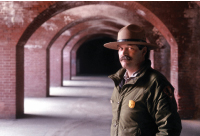

John A. Martini, National Park Service ranger emeritus and current author and historical consultant, will mark the 150th anniversary of Fort Point with “Sentries at the Golden Gate: From the Gold Rush to the Cold War” on Tuesday, May 10, at the Fort Mason Conference Center (Laguna Street at Marina Boulevard). A reception at 7 p.m. will precede the presentation at 7:30 p.m.

A nationally recognized military authority, Martini is the author of two books on military sites in the Bay Area: Fortress Alcatraz and The Last Missile Site.

Defending the Golden Gate

The Army’s original plan was to build a harbor defense port consisting of Fort Point, Alcatraz Island and Lime Point, which is located under the Golden Gate Bridge’s north tower. Building a fort on the Marin side of the Bay failed, however, which prompted the military to strengthen its forces at other sites, especially Alcatraz.

“The army couldn’t come to an agreement with the landowner on a purchase price for Lime Point. They dickered around so long the Civil War came and went,” Martini explained. “By the time the Army purchased Lime Point in 1866, the vulnerability of brick forts had become obvious to military designers, so they never built one on the Marin shore.”

The United States government bought the Lime Point reservation for the U.S. Army in 1866 because they could finally afford it – the owner’s asking priced plummeted after the end of the Civil War.

While Fort Point was physically located within the Presidio of San Francisco, it was its own “command” – an independent army post with its own commanding officer.

“In a way, the fort was actually a tenant within the Presidio,” Martini said.

shown here at Fort Point

Photo: courtesy John Martini

Martini points out that the former Letterman Hospital had a similar arrangement with the Presidio. “It was a totally independent U.S. Army hospital located inside the Presidio, but … operated outside the control of the Presidio itself. It had its own commanding officer who got his orders from the Army’s medical branch, not the Presidio.”

Preventing a Confederate Assault

During the first stage of construction, the cannons at Fort Point were faced toward San Francisco rather than the Bay or ocean. Groups of anti-Union sympathizers known as the California Column were present in the City, attempting to convince citizens to join the Confederacy. At the same time, Alcatraz Island, Yerba Buena Island, Angel Island, the Marin Headlands, and Forts Scott, Baker, Berry, Cronkhite, Miley, and Funston were preparing to launch weapons against any ship coming into the Bay.

In the end, the farthest west the Confederacy got was Arizona. The South had its eye on the Bay Area because it was thought to be rich in gold and silver, and known to be wealthy in the industries spawned by the Gold Rush; the area boasted waterfronts, factories, dry docks, and shipyards. There was much to protect in San Francisco, which had grown from a village of 500 in 1846 to more than 35,000 following the Gold Rush of 1848–1850. Fortifications of the area were so well known, however, and so respected and feared, that no Confederate soldier ever came close to penetrating the excellent defenses that had been established.

After California joined the United States in 1850, President Millard Fillmore signed bills that would have long-range ramifications for the Bay Area. According to Martini, one such bill saved parklands that still flourish today.

“The bill was ‘to reserve the following parklands in and around San Francisco Bay for public purpose,’” Martini said. “Today, those parklands are part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area or a state land, or a City of San Francisco open space such as Yerba Buena Island.” He adds that saving the parklands indicates that the building of Fort Point was part of a bigger story, which he teasingly promised to relate in his May 10 presentation.

The presence of artillery in and around San Francisco may have begun with the erection of Fort Point 150 years ago, but it did not disappear until the 1970s. The Bay’s fortifications from the earliest Spanish adobe batteries up through the Civil War fortresses culminated with the nuclear-tipped Nike missile sites installed during the Cold War.

Fort Point, according to Martini, provides a legacy for residents and visitors to share.

“It was built for wars that never happened and enemies that never came,” Martini said.

“Sentries at the Golden Gate: From the Gold Rush to the Cold War” is sponsored by the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society. Cost is free for members and $5 for nonmembers. For further information, call 415-537-1105 ext. 100, visit the historical society’s website (www.sfhistory.org), or send an e-mail to [email protected].