You say you don’t believe that time can actually fly? Then how do you explain the fact that a quarter century has passed since the Giants first opened the gates to their new ballpark at 3rd & King?

Originally called Pacific Bell Park, it has had several name changes over the years, before Oracle acquired the naming rights in 2019. To celebrate the milestone anniversary, members of the 2000 team were invited back for a reunion at home plate on Opening Day in April. Their skipper Dusty Baker stood in front of them and addressed the overflow crowd. “I remember our first year here, and it doesn’t seem like 25 years ago,” said the winningest manager in San Francisco Giants history. “But it’s been a great 25 years, and these guys behind me brought in the winning spirit with them from Candlestick. That spirit is still here and will always be here.”

Then slugger Barry Bonds took the microphone and asked those in attendance, “If you’ve been here for all of these 25 years, please stand up.” The response was akin to a standing ovation. Bonds continued, “I’ve got news for you. None of this would have been possible without your love, support and loyalty.”

When it debuted on the Major League landscape in 2000, legendary San Francisco Chronicle scribe Glenn Dickey wrote, “Pacific Bell Park will be the standard for all future ballparks, in large part because of the way it melds cutting-edge technology with classic ballpark design.” Over the years, the Giants made annual improvements — from high-tech updates to new menu items — so that at age 25, it never looked younger.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the park’s history is the chain of events that led to its creation. Former owner Bob Lurie tried many times during his tenure to pass a ballot measure for a new Giants home, but lost each time because expenditure of public money to build it was included in the appeal.

The closest Lurie came was in 1989, when his proposal seemed to have the proper momentum. But the Loma Prieta earthquake prior to the third game of the World Series against the Oakland A’s intervened, and the measure lost at the ballot box by less than a thousand votes. Wrote Dickey, “Opponents of the initiative said money should go toward earthquake relief, not toward a new ballpark.”

When two more initiatives, in San Jose and Santa Clara, both failed, Lurie looked at his annual losses at Candlestick Park and decided to sell the team to a group of Florida businessmen. Imagine the St. Petersburg Giants.

But when the MLB owners voted to allow the Giants to find new local owners, a group led by Safeway president Peter Magowan stepped forward to save the team for the City. Said Magowan, “Before we got approval, we had to assure the other owners that we would build a new park.”

During their first year in 1993, the Giants front office consciously decided not to publicly mention the idea of a new ballpark for the moment, but spent their energies on trying to improve the fan experience at what by then had been renamed 3Com Park. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, they plotted their approach to a new ballpark ballot measure. Said Magowan, “We were convinced that a ballpark initiative would never pass if it involved the expenditure of public money. It needed to be privately financed.”

The result was Proposition B, which passed by a huge majority, marking the start of a new age of Giants baseball. And so it was that Pacific Bell Park was christened on March 31, 2000, with the unveiling of the Willie Mays statue at the front door and a short series of exhibition games against the Brewers and Yankees.

The throngs who attended those “soft” openers formed concentric circles of constant movement around their team’s new home, soaking in the details, the vantage points, the playgrounds and gathering spots, and maybe watched the game a little bit.

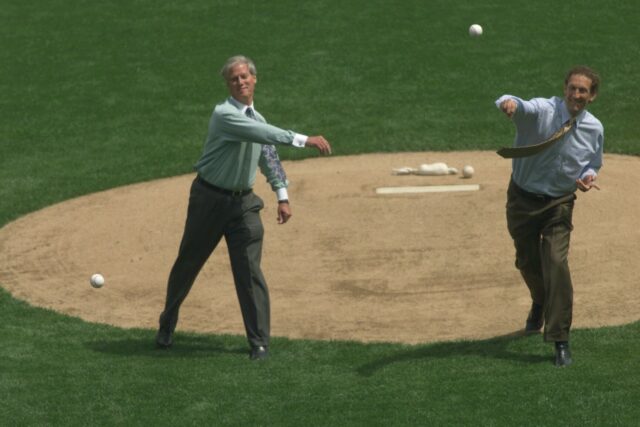

When the first regular season game was played on April 11, a full house of fans arrived with great expectations. But their hopes were dashed when the home team lost 6-5 to the rival Dodgers and continued to lose through the opening weekend, punctuated by an 11-7 defeat in the Sunday closer, when Stanford student Chelsea Clinton brought her dad to the game.

It was like an episode of The Twilight Zone, in which Magowan struck a deal with Satan, played by Sebastian Cabot, who granted him the ballpark of his dreams, then revealed, “But you will never win a game here,” with devilish laughter rising into the nighttime stars.

From there, however, the Giants righted their ship, and ranked among the league leaders in home victories while winning the NL West title by 11 games. Since then, the hundreds of sellout crowds have witnessed some of the most memorable moments in big league history, starting with the World Series championships in 2010, ’12 and ’14. They were there to watch Bonds strike his record-breaking 756th career homer on August 7, 2007.

They saw Tim Lincecum throw one of his two no-hitters and Matt Cain toss a perfect game in 2012.

Over the course of the past 25 years, Oracle Park has become more than just a spot to watch a baseball game. With the aroma of garlic fries, its signature scent, wafting through the air, it has become a place to celebrate the national pastime, San Francisco-style.

Comments: [email protected]