Rena Bransten Gallery is currently presenting “100 Years Without a Net,” a selection of paintings and works on paper in celebration of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday. The works in this exhibition celebrate Ferlinghetti’s long career as a painter, poet, intellectual, social justice advocate, community activist, and his deep commitment to art as a vehicle for cultural engagement.

The works reference other writers (William Blake and E. E. Cummings) and reflect Ferlinghetti’s thematic meditations on sexuality and gender; a world characterized by human isolation and alienation; and a desire for interrogating histories of industrialization and critiques of postmodern social realities through recurring iconic representations of human figures, birds, boats, skylines, and seascapes.

SORBONNE TO SAN FRANCISCO

It is important to situate Ferlinghetti’s painterly production within a remarkable personal history. He attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, earning a B.A. in journalism in 1941; earned a master’s degree in English literature from Columbia University in 1947; and went to Paris, where he earned a doctorate degree in comparative literature at the Sorbonne.

He served in the Second World War, spending four years on U.S. Navy ships, commanded a subchaser, was in the Normandy invasion, and saw the devastation of Nagasaki six weeks after the atomic bomb blast — all experiences that led to his radical pacifism.

After serving in World War II, Ferlinghetti moved to San Francisco in 1951 and cofounded City Lights Bookstore in 1953. As the owner of City Lights, he published works by many San Francisco Renaissance writers, aka the Beats, and was arrested for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in 1956. This resulted in a lengthy First Amendment trial — for which he was vindicated — and the poem, the poets, and he became widely known throughout the country.

It is in this context that Ferlinghetti is usually associated as a Beat poet — albeit

mistakenly — he self-identified as “an anarchist at heart” and stated, “I was never a Beat poet.”

This history and sentiments inform Ferlinghetti’s overall visual art trajectory. He first started painting while living in Paris in the late 1940s, with his work subsequently shown in galleries and museums nationally and internationally.

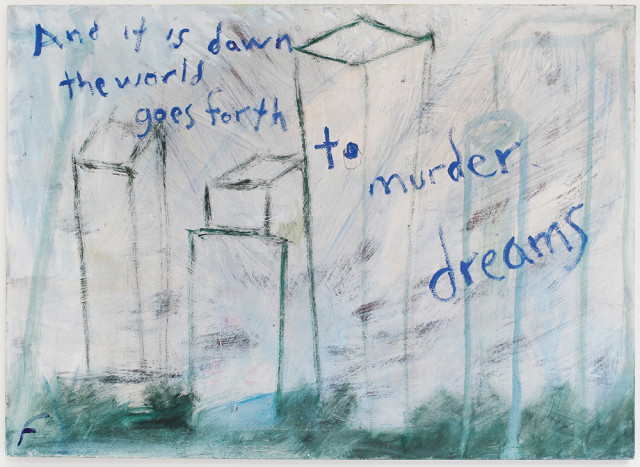

Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s And it is Dawn. Courtesy Rena Bransten GalLery

EXISTENTIAL UTTERANCES

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti: 100 Years Without a Net” showcases recent paintings and works on paper, and constitutes a continuation of his conjoining literary and art historical discourses through a fusion of figuration, abstraction, and textualization. In this exhibition, Ferlinghetti’s long affinity for Abstract Expressionism and concerns with what became known as Bay Area Figurative painting — a movement that fused Abstract Expressionism’s concern with extreme subjectivity, emphasis on essentials of medium and painterly process with Bay Area Figurative’s union of these formal concerns with figuration — is uniquely evident.

Here, Ferlinghetti’s paintings function as personal existential utterances aimed at articulating a desire for social commentary and transformation, manifested through his gestural painterly style and placement of textual references, which allude to historical, social, and literary themes that inform the content of the work.

This conflation of pictorial elements is evidenced in the works on display, as many seem to function as visual political placards, revealing a sensibility shared by many of the works — a kind of angst, estrangement, and discontent with contemporary life. Individually, the works function as emblematic assertions that are more concerned with making immediate personal statements than with concentrating on, or serving as vehicles for, “canonical” formal investigations of painterly prowess.

In fact, the impassioned expressionist gestures that are uniquely characteristic of much of the work reflect none of the virtuosity or subtlety that would suggest they are constructed with an eye toward painterly connoisseurship, and thus the viewer is not wholly seduced by form, color, or technique. Indeed, Ferlinghetti’s synthesis of a painterly dialectic of formal shapes and colors with figurative elements instead favor the articulation of personal sentiments that are socially and counter-culturally based.

Ferlinghetti’s utopian desire for social transformation is manifested in the works through the employment of art historical images and literary passages that bridge a false dichotomy to transgress demarcations between the visual and textual. The placement of text on some of the drawings and paintings reveals the nature of language and visual images as both material marks and socially legible symbols that simultaneously function as compositional elements and as slogans that infuse the images with historically specific references and meanings.

This strategy speaks to the interrelationship between art history and literature, and in the process raises the issue of how the construction of visual meaning is formed through literary interpretation and, conversely, the idea that paintings are “texts” that here can literally be “read” as personal and political statements.

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti: 100 Years Without a Net”: Tue.–Sat., 11 a.m.–5 p.m. (11 a.m.–8 p.m., Saturday, April 6) through April 27, Rena Bransten Gallery, 1275 Minnesota St. #210, 415-982-3292, renabranstengallery.com

Anthony Torres is an independent scholar, curator, and art writer.