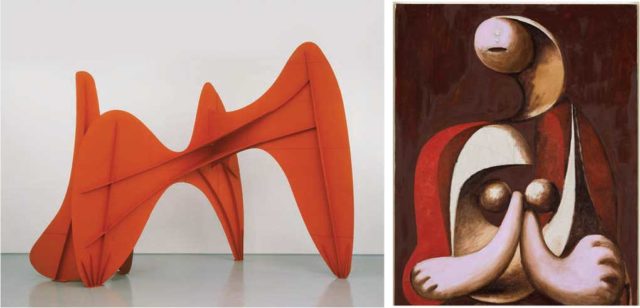

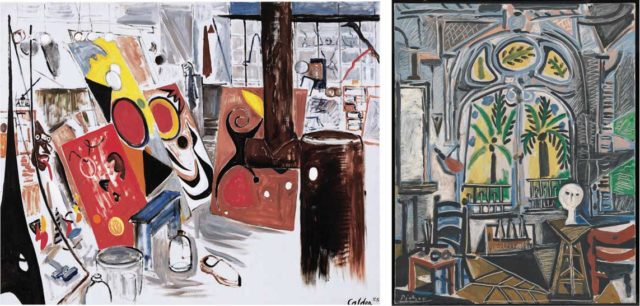

Works by two of the most influential artists of the 20th century, Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso, will be together in comparative exhibition. Not only the first of its kind in a major museum, the de Young is also the first museum in the United States to explore the artists’ relationship. In a visual conversation consisting of more than 100 paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs, the artists’ innovative approaches to subject matter, space, and composition reinforce their groundbreaking achievements in the realm of abstract art.

CALDER AND PICASSO

Alexander Calder is perhaps best known as the inventor of the mobile in which suspended abstract elements “drawn” in space become alive in a kinetic, three-dimensional change event of balance and harmony. Marcel Duchamp originally coined the term “mobile” in 1931 referring to both “motion” and “motive” in French. Early mobiles moved by motors whereas Calder created mobiles that responded to air currents, light, humidity, and human interaction. Similar to the Futurist art movement when motion translated as repetitive sweeping lines in paint onto canvas, the mobile was also influenced by industrialization and the rhythmic movements of machinery, commonplace in the world of manufacturing.

Pablo Picasso is considered one of the most influential and prolific artists of the 20th century. Working in a variety of styles and mediums throughout his life, he radically merged abstraction and representation as one of the pioneers of a new art form called Cubism. Picasso fearlessly tackled controversial subjects relating to the human condition, including love, sex, war, suffering, mortality, and death. One of his most iconic works is Guernica (1937), a painting giving depth to the horrors and brokenness of war, created in response to the brutal bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica by Nazi German and Fascist Italian air forces during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Creating an instantly recognizable painting style, Picasso’s influence became so great that it catapulted him into the world of celebrity, a distinction not commonly experienced among painters.

“Through his mobiles, Calder animated sculpture, embraced chance as a crucial artistic element, and engaged the viewer in a dynamic dialogue with the ever-evolving artwork. Exploring the concept of metamorphosis while alternating between representation and abstraction, Picasso revealed the infinite potential inherent in both styles — often in the same work of art,” states Timothy Anglin Burgard, distinguished senior curator and Ednah Root curator in charge of American Art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

A JOURNEY OF TWO PARALLEL VISIONS

Conceived by the artists’ grandsons, Alexander S.C. Rower and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, “Calder-Picasso” explores an exchange of works from the mid-1920s to the early 1970s. Thematically arranged, the similarities and distinctions of their art careers are mapped out in a journey through the Herbst Exhibition galleries. In the first gallery, the visitor is greeted by Picasso’s wire and sheet metal representation of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, titled Figure (1928). Calder’s Ball Player (ca. 1927) captures a figure reaching out into space during a moment of action.

The second gallery, “Drawing in Space,” is named from a phrase coined by critics for Calder’s wire sculpture in 1929. Line greets empty space or “the void,” a dynamic reminiscent of the space between musical notes or the pauses in the motions of dance in Calder’s Aztec Josephine Baker (1930), a wire sculpture representing the charismatic African American dancer, cabaret performer and legend of the jazz age in Paris during the 1920s.

THE VOID AND THE VOLUME

The play of negative space is expounded upon in the remaining galleries, including “The Void and the Volume/In Suspense.” Picasso’s Woman Seated in a Red Armchair (1932) minimalizes the figure into a series of floating shapes, disconnected yet positioned to suggest a female form. Similarly, Calder’s Little Yellow Panel (1936) explores the idea of a two-dimensional painting and a three dimensional element in motion.

Picasso’s Portrait of a Young Girl (1936) could almost be a painting of a Calder-esque sculpture representing a girl in front of water — a figure represented in tube-like shapes connecting with a repeated rhythm of line and, once again, void. Both artists explored and discussed in journals their ideas to expand the limits of volume and space in representation. In this exploration was a desire to strip form to its basic components as Picasso did in his bronze Bull’s Head (1942). The animal is reduced to a bicycle seat and handlebars rearranged with genius simplicity to evoke the head of the bull.

“We are delighted to share this fascinating exhibition with audiences on the West Coast,” said Thomas B. Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. “It reaffirms the revolutionary impact of their work, as each grappled with the representation of form, space and time, in art — and in doing so, redefined the conception of art itself.”

Calder-Picasso: through May 23, 415-750-3600, famsf.org. The exhibition will be available for in-person viewing when the museum is able to reopen according to state guidelines.

Sharon Anderson is an artist and writer in Southern California. She can be reached at mindtheimage.com.