Recently I was thinking about Richard Brautigan, the counterculture novelist and poet who hung out in North Beach in the 1950s and 1960s. I was cutting across the grass in Washington Square on my way to lunch, and I passed the bronze statue of Benjamin Franklin in his knee britches and frock coat. I stopped for a moment and envisioned Brautigan leaning against it just as he appears on the cover of his novella, Trout Fishing in America. And although I barely knew Brautigan, on that day in Washington Square I missed him. He added a loopy edge to North Beach. He could be charming one minute and irascible the next.

I saw him one day many years ago at Enrico’s on Broadway. He was sitting at an outdoor table with friends. He wore his usual costume: western outlaw attire, and a strange, broad-brimmed, fawn-colored felt hat with an exaggerated high dome. The complete Brautigan package included a long, droopy handlebar mustache and granny glasses. Because we had a nodding acquaintance from seeing each other around the neighborhood, I walked up to say hello. He stood, held out his hand for me to shake, and tipped that kooky hat in a courtly manner, and we talked for a while. It was one of his good days. Frequently Brautigan could be just the opposite of courtly — testy and irritable. He was like a trap full of crabs ready to snap. The man had a habit of looking askew at the world, but I couldn’t fault him for that.

THE BUBBLING LITERARY SCENE

Richard Brautigan was born in Tacoma, Wash., in 1935 and grew up in the Pacific Northwest, first in Tacoma and later in Eugene, Ore. He came from a broken home, a poor family with a mother who worked as a waitress. He never knew his father. He never attended college. He wanted to be a writer.

In 1955, he came to San Francisco and associated with the Beats. He contributed his poems to small, local publications, and tried to make ends meet. Before fame and some fortune found him, he delivered Western Union telegrams, sold his blood for cash, and worked in a chemical laboratory while he surveyed the bubbling literary scene. In North Beach, he met heavyweight poets like Michael McClure, Jack Spicer, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Philip Lamantia.

BLABBERMOUTH NIGHT

Those were heady days. Poetry was being read aloud in North Beach joints like the Cellar, then on Green between Grant and Stockton, where it was recited to the accompaniment of live, improvised jazz. Kenneth Rexroth, poetic guru of the time, said, “If we can get poetry out into the life of the country, it can be creative. Homer or the guy who wrote Beowulf was in show business. We simply want to make poetry part of show business.” Brautigan was show business personified. He fit right in. He recited his poetry on street corners and attended Blabbermouth Night at the Place on Upper Grant, a Beat club where you could read your work or just sound off about whatever was on your mind. He also liked to hang out at the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, a Beat haven at Grant and Green.

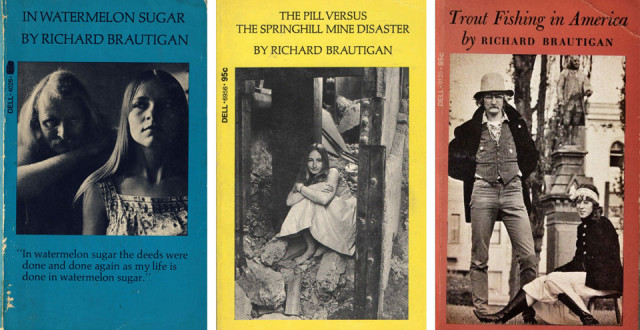

Brautigan bridged the gap between the Beats and the hippies. He was the hippies’ chosen icon but he drank like a Beat. By this time, his poetry was being published here and there, and in 1964, he published his first novel, A Confederate General from Big Sur. The hippies loved it. It was outrageous and outlandish, a disjointed satire on the hippie life. Other novels, stories and poetry followed, including In Watermelon Sugar, 1968, and Trout Fishing in America, which he wrote in 1961 but wasn’t published until 1969. These remain his best-remembered books, although he wrote 11 novels. He received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in 1966 and ’67, he served as poet-in-residence for the California Institute of Technology.

UNDERGROUND IN MONTANA

He once wrote eight poems that were printed on seed packets and sold under the title Please Plant This Book. At that point, his work was immensely popular and sold well. He spent some time in Japan where he was lionized, and then in the 70s, he moved to Montana and went underground.

He had a place in Livingston, Mont., along Pine Creek, and there he hung out with neighbor novelist Thomas McGuane, who in a quarrel once told him, “You’re nothing but a pet rock … a hula hoop. You should get down on your knees everyday and thank God for creating hippies.” Brautigan’s visitors to his Montana wilderness included such louche and loose characters as actors Rip Torn, Dennis Hopper and Jeff Bridges, and rock singer-songwriter Warren Zevron.

HAPPINESS IS A WARM HIPPIE

By 1984, everything was crashing down around Brautigan’s ears. He felt neglected; his work was being ignored, and he didn’t know how to recapture the exhilaration he had felt when he was a young North Beach literary giant. Jonathan Yardley, Pulitzer Prize-winning book critic for the Washington Post, said Brautigan was “… the Love Generation’s answer to Charlie Schultz. Happiness is a warm hippie,” he added.

When I first picked up Trout Fishing in America in 1969, I thought I was going to be reading a trout-fishing guidebook. Instead, I found lyric passages, much about trout, trout streams, and creeks. Brautigan was obsessed with trout. As I read along, I was perplexed. The narrative took me places I had never been. It includes anecdotes — quirky and a bit childlike — from his life, laced together with offbeat and dreamy observations. He once wrote, “I’ll think about things for 30 or 40 years before I’ll write about it.” That’s not only chronologically untrue, but Brautigan’s prose reads like it popped out of his head and onto the paper at just that moment.

THE ABSOLUTE END OF TWILIGHT

Brautigan committed suicide Sept. 14, 1984 at the age of 49. He was no longer the darling of the hippies. He had begun to lose it just as the hippies lost it.

He had run into an old girlfriend, San Francisco artist Marcia Clay. Let’s have Marcia wind up the story as she told it to me:

“I met Richard in the mid-seventies in a North Beach club called Dance Your Ass Off at the corner of Columbus and Lombard. I was there one night, and I danced with him. He danced like a cornstalk in the wind. That led to a long friendship between us. We dated, and he took me all over North Beach. He encouraged me with my painting and my writing. At that time, he considered me his girlfriend, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to be that. It was clear that he had personal demons. He was a flawed but wonderful guy. Those were exciting days for me. Then he married and was later divorced and was out of my life.

“In 1984 I ran into him at Enrico’s and he asked me to call him at his Bolinas hideaway in a few days. I called him on Sept. 14, 1984, and he said he was writing again and wanted to read to me from his new book, which he called, ‘The Absolute End of Twilight.’ He asked me to call him back in a few minutes; that would give him time to find the lines he wanted to read to me. I did, and I got his answering machine. I called and called, and each time the machine answered. Something was wrong.”

It is widely believed that Marcia Clay was the last person to talk with Brautigan before he shot and killed himself with a borrowed .44 caliber handgun. He once wrote, “The act of dying is like hitchhiking into a strange town where it is raining and you are alone again.”