Now on view at the Museum of the African Diaspora is Second Look, Twice: Selections from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation. The exhibition features the work of 15 acclaimed artists working in the medium of printmaking. Their art seeks to blur and move away from “essentialist” notions that make general assumptions regarding the work of artists of African descent and that focus on ethnicity as being central in constituting a particular “type” of art. Second Look, Twice, by contrast, highlights the diversity, variety, and specificities of the work within this group of artists.

Here, the diverse constellation of works — by Louisiana Bendolph, Loretta Bennett, Bob Blackburn, Mark Bradford, Willie Cole, Leonardo Drew, Ellen Gallagher, Sam Gilliam, Jr., Glenn Ligon, Gary Simmons, Martin Puryear, Lorna Simpson, Mickalene Thomas, Julie Mehretu, and Kara Walker — serves to illustrate that the work of artists of African descent engages myriad subjects in individual ways that defy the categorization and characterizations of the work based in others’ notions of race.

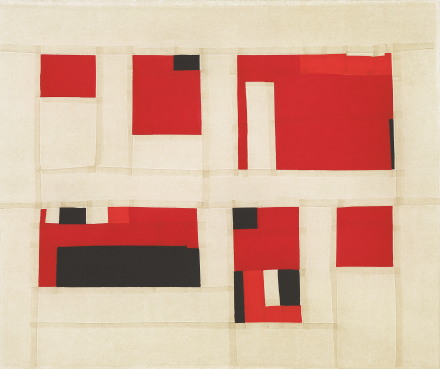

Louisiana Bendolph. (2007) Shared Legacy, softground aquatint etching. Courtesy Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

In fact, the artistic offerings demonstrate highly specific individual print practices that anchor MOAD’s philosophical orientation: that the “origin of the species” in Africa, and the African diaspora across global terrains and histories, has affected world societies and cultures, and that African diasporic movements have been integral to forging new identities, shared senses of place(s), and the formation of new social realities and communities.

That said, space does not allow for full engagement with the various works on display in Second Look. However, I would like to comment on several aquatint etchings by Louisiana Bendolph (b. 1960) and Loretta Bennett (b. 1960), descendants of Alabama’s famous Gee’s Bend quilters, as a way of addressing the significance of the various works on exhibit as condensed emblems of shared histories that bind our American and global histories, however different.

The etchings on display are the result of collaborations between the artists, Bendolph’s family, and the Gee’s Bend quilters. The textile-to-paper translations, via the medium of print, can be thought of as symbolic forms that pay homage to ancestral histories by referencing the exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, which traveled to various museums and was presented in 2006 at the de Young Museum.

The quilts that appeared at the de Young brilliantly demonstrated the quilters’ ability to translate harsh cultural experiences into personally useful and satisfying things of beauty. Indeed, the allusion to The Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition is relevant, because it illustrates how the past informs the present, as it honors the ability of a small group of quilters from Gee’s Bend, Ala., to resurrect, through their resilience and ingenuity, inherited knowledge that all too often is excluded from academic and institutional histories of art — such as the quilting tradition of Gee’s Bend.

The etchings also conjure the visual vocabularies of the Gee’s Bend quilters, descendants of slaves, who endured lives steeped in an intimate knowledge of physical and spiritual hardships, and who created utilitarian art objects that serve a similar function as art and music — to comfort, inspire, and uplift needy and exhausted bodies and souls.

Reflecting on Second Look, and how social histories inform art, the words of the late great poet, musician, and songwriter Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘Bicentennial Blues’ come to mind, as they reference cultural genealogy as a way of informing our lived realities:

But, the blues has always been

totally American

As American as apple pie

As American as the blues

As American as apple pie

The question is why?

Why should the blues be so at home

here?

Well, America provided the

atmosphere

America provided the atmosphere

for the blues and the blues was born

If “the blues was born” on slave ships, as Gil Scott-Heron said, then so too are the histories that informed the quilting tradition of Gee’s Bend and the work on display in Second Look, and histories of the African diaspora, in which we all share and are implicated, in one way or another, whether we know it or not.

Second Look Twice: Wed.–Sun. through Dec. 16, $12, Museum of the African Diaspora, 685 Mission St., 415-358-7200, moadsf.org