On July 9, 1846, Commodore John D. Sloat, commander-in-chief of United States Naval Forces in the Pacific, arrived at what would later be called San Francisco aboard his sloop of war, the USS Portsmouth. He went ashore and raised the American flag in a dusty plaza in the tiny Mexi-can village called Yerba Buena.

A few days later, a group of Mormons led by Samuel Brannan, a printer from New York, arrived aboard a chartered vessel, the Brooklyn, on which they had traveled around the Horn and over to the Sandwich Islands. There he armed his Latter Day Saints with rifles and set out for the Golden Gate. Brannan brought with him a complete flourmill, a printing press, and considerable moxie. It was his intention to start a Mormon enclave here. But at about the same time, Brigham Young and his followers crossed the Rockies and discovered the Salt Lake Valley, and that was that.

A gambler, big spender and wheeler-dealer, Brannan’s followers accused him of misusing funds he managed, and that was the end of his Mormon dream. Instead, he became a publisher of San Francisco’s first newspaper.

However, before Brannan got around to his publishing venture, Walter Colton, a former U.S. Navy chaplain who had become alcalde, or mayor, of the California capitol of Monterey, and Dr. Robert Semple, a dentist there, became the state’s first newspapermen. On Aug. 15, 1846, they published the Californian, a weekly devoted largely to shipping news. It appeared for nine months, half in Spanish, and half in English.

PUBLICIZING THE GOLD RUSH

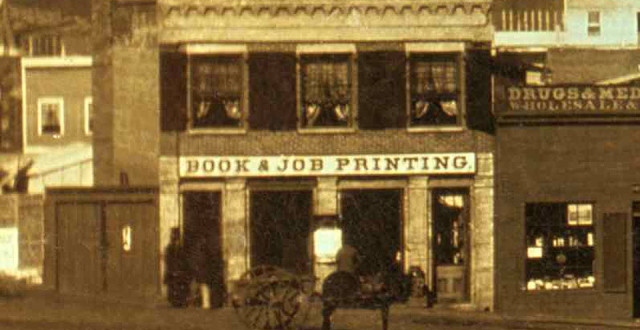

The discredited but resilient Sam Brannan did succeed in publishing the first newspaper in the tiny bayside village of Yerba Buena on Oct. 24, 1846, thereby becoming the father of San Francisco journalism. He printed a crude newssheet called the California Star and handed it out free. A few months later, he proclaimed the paper a weekly journal “devoted to the Liberties and Interests of the people of California.”

(For perspective, by 1775 there were 37 newspapers in America. And by 1816, there were seven daily papers in New York City alone.)

Brannan’s weekly was soon joined by Monterey’s Californian, which moved north and in May 1847, there were two newspapers in what by that time had been named San Francisco. In November 1848, the California Star and the Californian merged, and in January 1849 the little weekly was renamed the Alta California. It became a daily in January 1850.

When gold was discovered on Jan. 24, 1848 at Sutter’s Mill, Brannan not only published the startling news, but he shouted it in the streets and took off for the gold fields himself. He opened a store in Sacramento and became a publicist for the California Gold Rush.

MANY MORE NEWSPAPERS

Between 1850 and 1860, there were dozens of newspapers in San Francisco as the population exploded. They started up, merged and collapsed with regularity. In addition to newspapers for the English speaking, there were also French, German, Spanish, Chinese, and Jewish publications. In 1851, the Golden Mountain News, a Chinese weekly, was founded. The French weekly L’ Echo du Pacifique was founded in 1852. That same year, the German weekly, Staats Zeitung, started. In 1857, San Francisco’s first Jewish newspaper, The Gleaner, was published.

DUELS AND DEATHS

Journalism in those days was rough and tumble and frequently dangerous. J. F. Dunn, editor of the California Police Gazette, founded that paper in 1854, and was murdered a few weeks later by a printer in his office. Many editors carried the Old West’s favorite equalizer, the Colt 44. Vigilantes roamed San Franc-isco battling crime.

James King of William, editor of the Bulletin, was murdered in 1856 by a machine politician, James Casey, at the corner of Montgomery and Washington streets. Casey and a cellmate, Charles Cora (a gambler who had recently killed another San Franciscan), were taken from jail by the Vigilance Committee and were brought to trial in Fort Gunnybags, the committee’s headquarters on Portsmouth Square, where they were convicted and hanged.

Duels, known as the code duello, were common and frequently involved newspapermen who were quick on the trigger. (There were no newspaperwomen in those days.) General J. W. Denver (the Colorado capital would be named for him) was involved in a duel with Edward Gilbert, a senior editor for the Alta California, who was killed. C. A. Russell, editor of the Evening Picayune, engaged in a duel with Captain Joseph Folsom. Both missed their target, and they took out after each other with Bowie knives. The result was some serious slicing. A sign over Russell’s office door read “Subscriptions received from 9 to 4; challenges 11 to 12 only.”

DEATH BY REASONABLE CAUSE

The de Young brothers’ Dramatic Chronicle, which got off the ground on Jan. 16, 1865, managed to scoop other San Francisco newspapers in April that year with news of Lincoln’s assassination. Three years later, in September 1868, the brothers (Charles and Michael) dropped the word “dramatic” from the masthead and launched the Morning Chronicle. They were well on their way. They even put forth a mission statement that read: “We propose to publish a bold, bright, fearless and truly independent newspaper, independent in all things, neutral in nothing.”

In April 1880, apparently still “fearless, independent and neutral in nothing,” Michael de Young took over the paper when Charles was shot and killed by the mayor’s son after a long and very public argument that spilled onto the pages of the Morning Chronicle. The perpetrator was acquitted on grounds of “reasonable cause.” It was an interesting time to be a newspaper editor.

1906 EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT

The same year the Chronicle began, 1865, the Examiner came into being. It was the continuation of an earlier publication, the weekly Democratic Press. The Examiner was a weekly as well, but in 1880, it changed to daily publication. Soon, the Chronicle and the Examiner became dominant.

When the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed much of San Francisco the Call, the Chronicle, and the Examiner were burned out. They joined forces to cover the catastrophic event and got out a paper across the bay on the presses of the Oakland Tribune.

But perhaps the best newspaper story on the 1906 earthquake and fire was written by a journalist who wasn’t there at all. Will Irwin, a San Franciscan and ex-Chronicle man, had joined the New York Sun, and the paper had trouble getting copy for the story. Irwin wrote the “eyewitness” account while sitting at his typewriter in New York.